Constance and Kimberly Blaeser at the Write On, Door County “Writing the World” conference, May 2025

Hello, and welcome to The Burning Hearth! I’m so excited to share my interview with former Wisconsin Poet Laureate Kimberly Blaeser. (Click on her name for all things Kimberly and her full bio.) Kimberly is a Native American writer, photographer, and scholar, who, on very short notice, agreed to an interview in recognition of Native American Heritage Month.

As I sit here looking out my window at the aftermath of an early winter storm, I’m reflecting on this past May when I had the pleasure of meeting Kimberly. We were both presenting at the Write On, Door County “Writing the World” conference and, next to hoping attendees would enjoy my presentation, I arrived at the conference with the hope of meeting her.

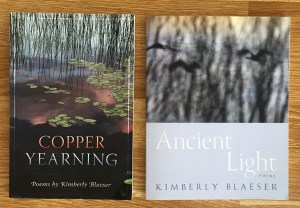

I have her collections Copper Yearnings and Ancient Light, both of which are balms to my soul. At once I am drawn in by her voice and her lyricism. And then, I’m left lost in thought, reflecting on her incorporation of the natural world; not as the other, but as a part of the whole of which we are all a part of. I told myself, if meeting her was meant to be, it would happen. Imagine my surprise, when I turned around at a gathering for the presenters to find her standing next to me. What a gift to meet someone whose writing I admire so much! Our meeting at the gathering led to many conversations over the weekend that I will always carry with me.

Meeting Kimberly, who is spirited energy from head to toe, was the highlight of my year, and having her at The Burning Hearth is the perfect way to close out my 2025 season.

Interview with Kimberly Blaeser

BH: Let me begin by thanking you for joining me at The Burning Hearth. It is so wonderful to have you here in celebration of Native American Heritage Month, and for my final post of 2025. I can’t think of a better way to close out my year. I would like to begin our interview discussing Indigenous Nations Poets (readers can link to it here), of which you are the founding director. The organization’s mission statement reads:

“Founded in 2020, In-Na-Po—Indigenous Nations Poets—is a national Indigenous poetry community committed to mentoring emerging writers, nurturing the growth of Indigenous poetic practices, and raising the visibility of all Native Writers past, present, and future. In-Na-Po recognizes the role of poetry in sustaining tribal sovereign nations and Native languages.”

I would love for you to share how In-Na-Po fulfills its mission statement, as it is a most profound and restorative gift to be able to offer to Indigenous people in a world where some are still uninterested in, or in denial of, what it means to have a peoples’ language and culture taken from them.

KB: Miigwech for inviting this conversation.

Indigenous Nations Poets undertakes various activities including an annual mentoring retreat where sixteen emerging writers have the opportunity to study with distinguished poetry faculty and build peer relationships. The retreat includes workshops, craft talks, engagement with local cultural sites, inter-art activities, and public readings. For every retreat, In-Na-Po also provides roadmaps for writerly activities such as submissions, public readings, and publishing. For each themed retreat, we produce double-sided poem cards featuring fellows, faculty, and visiting writers; and, at our 2023 retreat, created a short poetry-film “Poems for a Tattered Planet.” Themes have included eco-poetry, #languageback, and spirit lines.

We understand the liberation that writers from tribal communities experience when they gather together in a physical or virtual space with other writers with similar backgrounds. They finally find they neither have to explain their history, defend their identity, nor justify their literary aesthetic. They can simply write. The retreat embraces Indigenous values and aesthetics and encourages participants in their use of Indigenous languages.

In addition to these week-long retreats, we offer virtual follow-up programming, host AWP events including an off-site reading, and share opportunities that arise with the community of writers. We also consult with and support other organizations in their efforts to locate, feature as performers, provide workshop opportunities, and publish Indigenous poets, or to disseminate the work of Indigenous poets. For example, we have partnered with several organizations including Sewanee Writers’ Conference and Fine Arts Work Center to make scholarships available to their writing conferences. Another of our important collaborations is with Poetry Northwest and the James Welch Prize. Each year we co-sponsor and help to judge this contest for emerging Indigenous poets. The recognition includes a broadside, monetary prize, and celebration reading. This partnership will enter its sixth year in 2026.

In-Na-Po undertakes other strategic projects and programming. We recently created a pilot project, “#LanguageBack: Poetry as a Tool of Indigenous Language Revitalization,” to serve individuals wishing to work on their skills in the Indigenous languages of Menominee, Mahican, Oneida, and Anishinaabemowin. We partnered with teachers of those specific Indigenous languages and held day-long workshops in two tribal communities.

In-Na-Po recognizes the way language learning and teaching through poetry supports both the sovereignty of tribal nations and our survivance as Indigenous peoples and protectors of the planet. Because the language carries important teaching—environmental, spiritual, and subsistence teaching (among others)—using the language in poetry can also carry that Traditional Indigenous Knowledge into the world at a time our planet desperately needs it.

In conjunction with the pilot project we created two films, the first of which, “College of Menominee Nation Language Back Workshop,” is available on our website and on our YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KD6uDo9B3Ao. A second short documentary film “Language Back” https://filmfreeway.com/languageback is currently included in more than a dozen film festivals.

As an additional follow-up, I entitled the Spring 2025 issue of Yellow Medicine Review I edited “Indigenous Writers taking #LanguageBack.” It includes In-Na-Poets as Associate Editors and features the work of writers from thirty-one tribal nations.

We have many ideas for new projects and for expanding the reach of our work as funds become available.

BH: How does oral storytelling differ from written storytelling, and why is it important to keep oral storytelling alive?

KB: I love that you use the word “alive” in your question, because oral literature is animate (alive) in ways that written literature cannot be. This comes through active engagement with the listener. The response of the audience can impact the performer and inflect the story. Oral works adapt to the contemporary circumstances—to the physical place in which stories might be told, the make-up of the audience, and the social climate of the moment, for example. An audience helps “make” the story.

For these reasons, oral storytelling becomes a more communal act. The storyteller remains responsible to their audience in ways more immediate than a print text can. They share their story while receiving input in real time during their performance. I think of storytelling as involving reciprocity.

BH: I have your collections Copper Yearnings and Ancient Light. In keeping with my promise to limit my questions, I decided to select a poem from your most recent collection Ancient Light, to discuss with you. The collection’s title alone starts me wondering and pondering.

After struggling with selecting a poem to discuss, I decided to close the book, open it randomly and see where I land. (This is becoming a common practice of mine when interviewing people with a short story or poetry collection.)

I must admit, I was excited when I opened the book to “As if my now gloved hands were secrets.” While there are many things to touch on in this poem, there are two lines that have taken up permanent residency in my mind. They elicit a “Yes!” from me every time I read them or think about them. The lines are:

“As if pencil were a penicillin,

poetry a contagion of compassion.”

The lyricism of these two lines is simply masterful. What a wonderful earworm that in its repetition, the suggestion of making a pencil an instrument of healing, and the spreading of compassion through poetry like that of a contagion, begins to transform the person infected by its song. Or at least it does me. It causes me to think about the true power of writing and how it can create powerful, positive change in a person. Which leads me to the last two lines of the poem, and why I have been so drawn to poets like you lately, as well as Joy Harjo, N. Scott Momaday, and Ada Limon. You are all poets and writers who unite the natural world with our existence. You demonstrate our need to connect with, and open our hearts and minds to, the fact that all of us, each and every one of us, are bound together by our shared existence with the largest living organism among us, the earth. And, as the last two lines demonstrate, wonderful things can occur when we are moved by its rhythms.

“As if flood of wetlands were an allegory for hope.

As if we were seeping close closer –nodistance.”

What does seeping closer until there is a nodistance mean to you?

KB: I wrote this poem during the pandemic, so it “means” on several levels. Some of the imagery arises from that time when we were distancing, when we were searching for where we might find safety from the virus, find healing. The larger healing needed during that time was underscored, of course, by the murder of George Floyd. Hence the longing for compassion and hope. But the “nodistance” you ask about alludes not only to the time post-pandemic when we can again, safely, be in close contact; it alludes to the need to break down artificial barriers like race and class.

As you suggest, this poem also draws upon natural imagery—here the flooded wetland seeping closer. But more broadly, it invokes the wisdom of the natural world. The nearer we place ourselves to that source, the more able we become to create a livable future, to align ourselves with sacred rhythms .

Kimberly Blaeser reads “As if my now gloved hands were secrets”

BH: When we met at the Write On, Door County’s “Writing the World” conference this past May, you said you were moving into long form writing. If you can and are willing, please share how it’s going.

KB: Yes, though I will never abandon poetry, I’m writing more prose—both fiction and creative nonfiction. It has been fun stretching into these genres, and I have had several exciting developments related to this work. For now, I can only tease you with that vague statement, but please keep an eye out for an announcement soon. Meanwhile, you can find my story “Waiting: A Quintet” in a recent Keyon Review issue and through their website. I won the Master’s Review’s summer short story competition in 2025 for “Leaving Paradise” and my CNF piece “Wars and Small Wars” that just came out in Water Stone Review was nominated for a Pushcart. Plus, I’ll have a story in the Indigenous Never Whistle at Night Part II when that comes out next fall and I’m continuing to simply enjoy the writing!

BH: I want to end our interview on the water surrounded by trees. In your biography section of Copper Yarning, it states that you spend part of each year in a “water-access cabin adjacent to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness in Minnesota.” Copper Yearning came out in 2019, and so I’m wondering, do you still do this? Please speak to what the beauty of the Boundary Waters landscape and the remoteness of the place does for your soul and for your writing.

KB: Yes, we are blessed to be able to still spend time in the BWCA region and have been doing so in the summer and fall for more than twenty-five years. We have begun basic upgrades on our cabin (like adding insulation) so we may soon be able to make some winters visits.

The days, weeks, and sometimes months we get to live there count as spiritual healing time for me. I am often in the kayak on the water with my camera and notebook, exploring and falling into another world and another sense of time. The dance of light and water never repeats in exactly the same way—and it never gets old. During the “golden” hour just before dusk reflection doubles everything and sometimes I wonder which is more real—the above water world or the one I see reflected in its depths.

I treasure all our encounters with natural creatures—moose, bear, river otters, mink, pine martens, eagles, herons, swans, grouse, and at least a dozen other kinds of birds who come by. Beyond the simple joy in observing the different creatures, the watching has different kinds of rewards. It resets us in some way—maybe loosens the tension that has built up from endless deadlines and hurried travel, maybe awakens dormant instincts. I don’t know how to characterize or measure the change, but the effect is priceless.

Nights we lie on the ledge rock and lose ourselves in the sky—its layers of stars and the flash of meteors. Occasionally while lying there, we hear the wolves howl. Of course, the loons’ song echoes across the waters and the beaver punctuates the night with the cymbal splat of its tail. When summer storms come, the thunder and lightning seem especially dramatic there over the water.

Life becomes an endless stream of sensations—the damp pine scents, the rocking on the waters in a kayak, the shiver of the uncanny as we watch fog dance across the morning lake. But perhaps most memorable are the moments when the ego disappears, when the sense of I dissolves into the immenseness of the place—a million wet acres where we become nothing but another being who belongs.

Every moment is a poem—how could I not but write?

That is the perfect note to end this interview on. Thanks so much to Kimberly for this awesome, inspiring interview. Good luck to her, her writing, and In-Na-Po in the coming year.

This is my final post for this year, so I would also like to thank all the wonderful people who have joined my this year: Isaac Yuen, Kristen Tenor, Andrew Porter, Al Kratz, and Jai Chakrabarti. I am so fortunate to have been in conversation with such talented people.

To all of you who stop by and read my posts, thank you! I hope your coming year is filled with sunshine, calm winds, and time to be outside.

The oak tree and me, we’re made of the same stuff. –Carl Sagan

All my best,

Constance