Hello and welcome to The Burning Hearth! I am thrilled to share Issue One of Voices of the Summer Solstice with you. This is a small but mighty collection of writers, and I’m honored they agreed to contribute to this issue.

Diane Gottlieb, Cathy Ulrich, Susan Leary, and Susan Triemert write on the theme “What Blooms.” As I was formatting this post, I was struck over and over again by the beauty within these pieces. Each writer deftly renders the theme, and their stories and poems left me with a stirring deep within my core. The blending of their voices is truly a harmonized chorus. You, reader, are in for a treat!

A special note before you begin. The beautiful artwork in this post was done by my dear friend, Sandy Urban. I asked her for an artist’s statement and she sent me her current mantra, which I love. Don’t do boring art ever again. An artist for decades, Sandy told me that she has had some success with doing what was asked of her artistically, and she’s grateful for that. But at this point, she shared, she’s exploring what speaks to her. This, in my opinion, makes her the perfect collaborator for “Voices of the Summer Solstice.” Enjoy!

You Will Grow from This

by Diane Gottlieb

My guardian angels show up

sometimes

in human form. Like Laura,

a healer whose deep-throated

Om—

could only

have swelled from the whale’s song of heaven.

She changed my life

with one simple question:

Do you know what you’re afraid to know? I didn’t

have a clue, so I breathed into the sun

and turned toward the fear

and discovered what I’d known

all along—

my husband had had an affair.

Om—

how that once-secret burned,

Om—

how Laura held me, her hands hot

Om—

on my shoulders, unleashing

once-trapped truths, flying now

on the wings of the free.

Marion, my Woodstock neighbor,

another guardian angel.

Years beyond my discovery, and right after

my husband’s death,

she drove to the police station

to retrieve his backpack

to keep it for me until I felt ready

to examine its contents—

Legal pads. Papers.

Scribbles in his illegible hand.

Pens and more pens, both black and blue—

the colors blanketing his face. My tears

watered those blue and black blooms,

as he lay on a gurney in the morgue.

My lips grazed his dark bruises, resting beside

slits of reddish brown. I tasted the salt

of dried blood. Markings,

where tiny slivers of glass

had embedded into his skin.

My guardian angels show up

sometimes

as images—

him lying there, oddly

at peace, wearing a loosened paisley tie.

My guardian angels show up

sometimes

as words—

words coming from nowhere,

appearing everywhere: You will grow from this.

My guardian angel shows up

as forgiveness.

When my husband died,

I would stare out our bedroom window at the stars.

I would walk in the mornings into the woods,

lean against one pine and then another,

press my great grief against their ground.

They’d hug me, those sturdy rooted guardians.

Those angels. Who stood tall

when I could barely stand.

Two Astronaut Love pieces

by Cathy Ulrich

A Handful of Daisies

The astronaut’s mother will die before the astronaut finishes her first semester of college. She will be ash and bone and something sharp in the corner of her daughter’s eye. She will be dead when the astronaut marries the girl from across the street in a ceremony where all of the old neighbors are invited, such lovely brides, they will all say.

But the astronaut’s mother is alive now and holding her daughter, not nearly two, and she will never have another child. She will never want another child, never be able to express the absolute perfection of her daughter, those curved baby cheeks, those stumble-steps, the ripple of her baby breath against her face.

The astronaut’s mother is alive and watching the new family across the street, the mother with her clutch of three sons. The astronaut’s mother doesn’t know any of their names, except the oldest boy, with his tendency to wander, the mother trilling it into the air: Arturo, Arturo.

The astronaut’s mother has seen the three boys around the neighborhood before, since their family moved in, three little round heads bobbing up and down along the sidewalk. They stay on their side of the street. Good boys, she thinks, who come when their mother calls them home.

But they have crossed the street today, standing at the edge of her lawn admiring the flowers when she and her daughter come out on their way to introduce themselves and offer a casserole (as she had been taught by her mother, it’s only neighborly).

What are these, says the oldest one, pointing.

Daisies, says the astronaut’s mother. She has been clipping them back before they die, placing them in glass vases in the center of the dining table, their round white faces shining out. Would you like to take some to your mother?

But the boys run off while the flowers are still in her hand. She almost takes them inside and puts them in a vase, but the house is already full of daisies, petals dropping to the floor, and so she takes her daughter in one hand and the flowers and casserole in the other and goes after the boys to their home. Their mother is waiting for them on the step, heavily pregnant and, the astronaut’s mother thinks, beautiful. She has never seen such a beautiful woman before.

The astronaut’s mother smiles at the woman across the street and her three little roundheaded boys, admires how easily she bends to pick up the littlest, even though she looks (as her own mother would say) about to pop. The astronaut looks at the round belly and says baby and the woman from across the street smiles in a charmed way: yes, baby.

Would you like to come in, says the new neighbor, holding the casserole, holding the daisies, but no, it is nearly time for dinner, and the astronaut’s mother takes her daughter by the hand and back across the street.

She will die before her daughter first goes to space, but she is alive for now, holding her little girl’s hand tight, watching that little baby hand reach for the sky, reach for something beyond the sky, beyond the blue, her perfect, perfect daughter. When they look back from across the street, the neighbor woman waves to them both, waves, waves, waves.

Only as Far as Ever

When the astronaut first goes to space, her wife learns all the parts of a shuttle. She recites them during the countdown, doesn’t look at the television screen. Watches her hands instead, the way they clench and unclench. Her mother calls when it is all over, when the astronaut is safely in the sky.

It was really something, wasn’t it, her mother says, and the astronaut’s wife can only answer with the names of metal.

Before they are married, the astronaut’s future wife goes to visit her at college. This is after the astronaut’s mother has died, after the for sale sign has sprouted like a dandelion in her old front yard.

The astronaut’s father tells her he’ll put her things in storage. Her things and her mother’s.

Fine, says the astronaut, and lays the phone on its side until the shriek of a disconnected signal makes its way across the line.

The astronaut’s future wife has a box of things the astronaut has asked for, a little suitcase of her own with cheerful orange flowers on the front. She rides the bus for two days with the suitcase under her feet, the box in her lap. She looks out the window and counts the blue cars that pass by.

The astronaut’s wife, while the astronaut is in space that first time, tends to the daisies in the yard. She has never grown anything but daisies, never roses, hyacinths, tomato plants. She waters the soil around them and sings the songs that the astronaut loves, the ones from the radio stations their fathers used to play. She watches their bright daisy faces turn up to the sky.

Before she leaves to visit the astronaut at college, the astronaut’s future wife helps her mother bake a pie. She recites the ingredients as she rolls out the crust; her mother smiles.

The pie gets wrapped in tinfoil and set atop the astronaut’s box of things.

Such a lovely treat, says the smiling mother, and gives her daughter a scarf to wear on her ride. Her father gives her a little pocket knife with a switch on the side.

In case anyone gives you trouble, he says.

The astronaut’s future wife nods, slides the little knife into the outside pocket of her suitcase.

The sky, while the astronaut is gone, seems so very far away. The astronaut’s wife knows, though, it is only as far as ever.

On the bus, there is an old woman with clacking crochet needles and a boy with something in his hands that goes beep, beep, beep. There is a man who keeps smiling at the astronaut’s future wife. He is missing one tooth; the rest are perfectly white.

He takes her by the elbow at one of the rest stops when she steps off the bus, careful there, he says, like she had been about to fall.

I’ll be careful, she agrees, and thinks of the little knife in her suitcase pocket.

The astronaut’s future wife gives the astronaut the pie first.

It’s sweet potato, she says, do you like sweet potato?

I can’t believe he’s already selling the house, the astronaut says.

It’s like he was just waiting for her to die, the astronaut says.

The astronaut’s roommate is gone for the weekend, gone home to her mother and father, two little sisters and a cat she is always telling the astronaut about. Her side of the room is quiet and empty, except for the shining, flat smiles from the boy-band posters she has hung up on the wall.

The astronaut’s future wife puts her arms around the astronaut. It is the longest they have touched, their childhoods filled with hand brushes and through-window-screen kisses.

The astronaut’s future wife holds the astronaut and thinks how there is something ephemeral and unreal about her, something that could easily float away, into the sky.

She thinks: I will never let you go. I will never, never let you go.

I Don’t Want to Write About Flowers

by Susan Leary

So much has to happen before a thing can bloom

& so much of what happens we never see. A sprawling narrative

that unfolds beneath the earth before there are scissors

or a kitchen table or the human hand. A flower is without history

because we think we know what happens: soil, seed, sun,

water, bloom. & even if laughter is considered, or drowning

or drought, or one seed’s envy of another, we forget

what the flowers may have endured before they were flowers.

Everyone sees our suffering & we must survive

to bloom while a flower runs its course, a phrase undressed

of meaning & I am exhausted by meaning. I am

exhausted by the beauty inside the sadness: the solitary flower

outside the jail or the crack of daybreak that slips

between the curtain. Beauty reveals the flawed functioning

of everyday matters, but we forget this, too. All that dirty water,

the chipped vase, the apartment’s shaded window. Yet, the flowers

are so well-adjusted. Set towards the sun, they seem to be creating

a language to talk to God. Greedy me, I pluck the flowers. I commit

a minor contentedness. I stow the words in my palm.

When the Skies Turned Sepia

by Susan Triemert

When her mother only had days to live–trickled down from weeks, and before that months–Charlotte knew what to do. As the sun dipped its rays into the murky darkness, she dove from the dock and sliced through the silent waves. Beneath the surface, clouds of fading sunlight fogged before her. If she’d remembered her fishing net, she would have scooped up the bleeding shades, corralled the colors before they faded further, before the darkest depths yanked them down. To extend her mother’s minutes on earth, she kicked the sun’s rays back up to the sky; shades of dusty salmon, golden daffodil, and aquamarine shot through the surface. Schools of sunfish flashed before her, thwarting her every move. She pulled back her pitcher’s arm and hurled beams of amber and indigo towards the stars.

Charlotte glanced back across the lake. She could see her mother stretched out on a lawn chair, staring back at the painted prisms, back at her. Was her mother recalling past sunsets? Was she remembering Charlotte tumbling across the waves as she learned to waterski, their diving contests off the swim platform, fishing outings at dawn? Were all those moments being spotlit here, framed by the dimming light? A marquee of memories.

Charlotte sensed she was losing this battle. She spouted fountains of rust and magenta from between her teeth, dolphin-kicked iridescent droplets until they arched back into the horizon. When all of her energy had drained, when the colors started to drip once again, she resurfaced. The world looked different. If night had turned black, dawn could have returned ablaze with color. Now, with her mother soon aglow only in memory, the sky saluted in a half-mast sepia.

Author Biographies:

Diane Gottlieb, is the editor of Awakenings: Stories of Body & Consciousness (ELJ Editions), winner of the 2024 IndieReader Discovery Award for best anthology, and the Prose/CNF editor of Emerge Literary Journal. Her writing appears or is forthcoming in Brevity, Witness, Colorado Review, River Teeth, Florida Review, Chicago Review of Books, HuffPost, 2023 Best Microfiction, and The Rumpus, among many other literary journals and anthologies. She is the winner of Tiferet Journal’s 2021 Writing Contest in nonfiction, longlisted at 2023’s Wigleaf Top 50, a finalist for The Florida Review’s 2023 Editor’s Prize for Creative Nonfiction and a finalist for the 2024 Porch Prize in the nonfiction category. Find her at https://dianegottlieb.com and @DianeGotAuthor.

Cathy Ulrich tends to kill most plants – not on purpose, though! Her work has been published in various journals, including It Has Pockets, trampset and Centaur Lit.

Susan L. Leary is the author of four poetry collections, most recently Dressing the Bear (Trio House Press, July 2024), selected by Kimberly Blaeser to win the 2023 Louise Bogan Award, and the chapbook, A Buffet Table Fit for Queens (Small Harbor Publishing, 2023), winner of the Washburn Prize. Her poetry and nonfiction have appeared or are forthcoming in such places as Indiana Review, Diode Poetry Journal, Crab Creek Review, The Arkansas International, South Dakota Review, Cider Press Review, Tahoma Literary Review, and Verse Daily. She holds an MFA from the University of Miami and teaches at Indiana University.

Susan Triemert’s collection of essays, Guess What’s Different, was published by Malarkey Books in May of 2022. She holds an MA in Education and an MFA from Hamline University in St. Paul, MN. She earned a Best Microfiction in 2022. She has also been nominated for a Best of the Net and multiple times for the Pushcart Prize and Best Microfictions. Her essays and stories have been published in places like Colorado Review, Gone Lawn, and Pithead Chapel. You can find her work at susantriemert.com or on X at @SusanTriemert

Huge bouquets of thanks to all my contributors.💐💐💐 You’ve made this the best summer solstice ever! And thank you, readers, for stopping by. I hope you’ve enjoyed Voices of the Summer Solstice. If so, please comment and share to support these writers and their work.

Coming up at The Burning Hearth: an interview with Tara Campbell (Tara’s piece “Would You, Empress” from Voices of the Winter Solstice II: The Ending Place was longlisted for the Rhysling Award) on her book City of Dancing Gargoyles (SFWP, September 2024), an interview with Shze-Hui Tjoa on her book The Story Game (Tin House, May 2024), and an interview with Kylie Mirmomahadi on her book Diving, Falling (Scribe, September 2024). I am stoked about this line up!

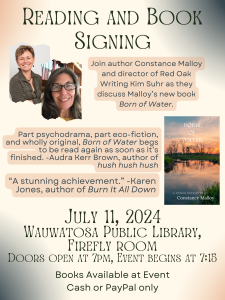

Lastly, my hybrid novelette Born of Water (ELJ Editions) has set sail. Click here for link to Amazon. If you are in the greater Milwaukee area and are free on Thursday, July 11, I will be in conversation with Kim Suhr, writer and director of Red Oak Writing.

P.S. Born of Water is dedicated to Kris Roberts, my childhood friend and soul sister who was abducted after leaving my home in 1981. If you haven’t read “Fourth and Ash” in Emerge Literary Journal, click on the journal to read the story. She will be attending this reading! I am so excited and beyond emotional. The day of the reading will be the first time we have met since I left her at the corner of Fourth and Ash. (Is there enough Kleenex in the world?)

Love, Laughter, and Peace to you all!

Constance

Ah, there is actual research that an artist’s best work is done for themselves and not commission work. Never ask an artist to create for you is what it comes down to. Love this piece!

LikeLike

So very true!

LikeLike