Welcome to The Burning Hearth. This month I had intended to interview Maggie Smith and discuss her debut novel Truth and Other Lies, but life presented me with a situation I had not anticipated, causing me to change what I wanted to focus on in this post. Maggie was more than gracious to forego our interview (I do so hope you will click on the link embedded in her name and give her and her novel a looksee.), so that I could share with my readers the story of my brother Reece, who is at the heart of the above-mentioned situation.

Born January 31, 1959, Reece Amos entered the world as an ABO blood factor baby. The shorthand definition for this: my mother has type O blood and Reece’s, which was either A, B, or AB, was incompatible. I’m not sure if it was because of this condition or not, but my brother required a blood transfusion when he was a few days old. Then, after more difficulties, it was discovered that he had a rare, and newly identified at the time, double-recessive gene disease called galactosemia. Shorthand for this: his body lacks the enzyme which allows for the breakdown of the simple sugar galactose, which is present in milk and dairy products. For Reece, having milk could lead to severe complications and even death. This meant that Reece would have a regulated diet for life. But the true implications of this disease, does not stop with just diet.

Reece’s mental and emotional development has been stunted by the disease, leaving him trapped inside of the emotions and mental state of a fifteen- to eighteen-year-old. My parents were told that he would be delayed in most things and would probably be highly uncoordinated. His coordination is one area he proved them wrong. Reece is ambidextrous and never met a sport he didn’t excel at.

I am seven years younger than Reece, and my life has been marked by growing up to, and surpassing him, in every aspect. As any sibling of a special needs person can attest, there is an inherent guilt one feels for having a “normal” life. I often wonder, though, if this would have weighed as heavily on the both of us as it did, and still does, had I been his older sibling.

One day when I was twelve and Reece was nineteen, I came home from school to find my parents outside face to face in a serious conversation. They made it nonverbally clear to me I was not to bother them. I went inside to find Reece laying on our sofa. He had an arm over his eyes and was crying. He explained to me that my parents had told him he could no longer be friends with two girls who lived down the street from us. These were the only friends my brother had. Supposedly, one of them was pregnant. Reece was not the father, but it was just that they were “those kinds of girls” as my mother later said, after telling me, “Your father and I are only trying to protect him.”

Before I knew that information, I was standing at the end of the sofa watching Reece cry, realizing, before he said anything, that I had already passed him in terms of the trust and freedoms I was granted.

He dropped his arm, lifted his head, and said to me the truest words I’ve ever had to accept in my life, “You will never know what it’s like to not have a friend. You will never know what it’s like for them to take your only friend away.”

One of the beautiful things about my brother is that he did not judge his friend for being pregnant. He liked her. She was his friend. The nature of her character could be debated all day, but she was Reece’s friend, and that was all he cared about.

He laid back and covered his eyes again.

I looked at him for several seconds and then did the only thing my twelve-year-old self could imagine was right to do: honor his truth by validating it. “You’re right,” I said. “I will never know that.”

I walked away awash in both the blessing and the curse of my reality and drenched in the suffering of my brother’s.

Amos (my maiden name), as many of you might know, is the name of a biblical prophet, who was the first to have a book in the Old Testament named after him. God sent him from the countryside with the task of warning Israel of its coming doom if those more fortunate did not change their behaviors towards those less fortunate.

He was, of course, ignored and dismissed as a foreigner: a shepherd who didn’t know the ways of the city. His unpopular, unwanted message made it clear to the people of Israel that their unjust, hypocritical ways would lead to punishment from God, if they did not heed his warning to change. I have read that more than any of the books in scripture, Amos holds God’s people accountable for their mistreatment of others.

One can imagine, as we see in our own society today, that message didn’t go over well. A persistent advocate for the oppressed and the voiceless in the world, Amos spoke out strongly that the physical and spiritual needs of all people mattered to God and that justice would be served.

If the biblical Amos was the advocate for fair and equal treatment, my brother Reece (who was often called Amos, given that both of his names can be either a first or last name) was the physical embodiment of the voiceless and the oppressed he advocated for. If there is one injustice that has been done to my brother (and there have been many) it is that he has never been allowed to speak for himself. He is told how he feels, what he will do, and how to respond to the injustices he has suffered.

If you’ve read my memoir Tornado Dreams, then you know mine was not a gentle childhood. For all the things I endured, Reece and my other two siblings endured more. But my other siblings and I have agency and facility where Reece does not, which has left him incapable of the one thing he has wanted most, just to live his life on his terms.

Now, sadly, all physical agency has been stripped from him as well. Two years ago, he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease. On February first of this year (the day after his 63rd birthday) he demanded my mom call an ambulance because he was “unable to get his legs to work” and feared he would not make it to the bathroom in time. For a whole host of reasons, (that are out of his control) this was something that should have happened weeks ago but did not. He arrived at the hospital, stayed for three days, is now in extended short-term skilled care, and will probably go straight from there to long-term care.

I went to Iowa two weeks ago to visit him. But before talking about that visit, I have one more early childhood story to share.

Up until the ages of five and twelve, Reece and I were the best of sibling buddies. And the last thing I remember doing with Reece as sibling buddies was learning to swim. And it strikes me that this experience is tied to the last time I remember my father healthily engaging with us in any real way.

Reece was deathly afraid of water, and I loved water but didn’t know how to swim. Considering that every Sunday my family and several others met at the Izaak Walton League lake for a full day of swimming fun, our need for being attended to hampered my parents’ fun; and if I’m honest, probably my two older siblings’ fun as well. So, every Monday evening, over the course of several weeks, my parents, Reece, and I headed for the Izaak Walton League for swim lessons. While my father helped us learn to swim, my mother grilled burgers and prepared a picnic dinner for us. Good times that resulted in my brother being more comfortable in the water and me saying goodbye to water wings.

Later that same summer, on a hot August Saturday, Reece and I were playing in my sandbox when my mother called me inside for my afternoon nap. (I still napped at five, still napped at twenty-five, and luxuriate in my naps now at fifty-five.) Before going inside, Reece and I made plans of what we would do when I woke up.

While it is a commonly used trope, I could not dismiss the feeling of dread that swept over me when I rounded the southwest corner of my house to go inside and saw dark, ominous clouds rolling in the sky out beyond the Des Moines River. I remember opening the door and thinking to my young self that something was very wrong.

After my nap, and oddly, no storm, I rushed outside to find my father standing on our patio. He told me Reece was at our neighbor’s. Eventually, Reece came from our neighbor’s yard, crossing the alley into our yard. Even from that distance, I could tell something was very different about him. It was his eyes. They were not my brother’s eyes. Not the kind, receiving eyes I had known before my nap but rather, closed (energetically speaking), agitated eyes that looked at me with an odd dismissal and ire. Reece has blue eyes, but my memory of looking at him in that moment was of looking at dark brown, impenetrable eyes. From then on, Reece became my antagonist. We never played again.

When I walked into my brother’s small room in the Ridgewood Care Facility, it only took one look at him to see whatever had entered him that afternoon long ago during my nap, had left. The young, vulnerable boy, who laughed easily and was always ready for adventure had returned. Only now, he wasn’t laughing, because he knew no matter how ready he was for adventure, his days of adventuring were over.

He was scared. He had no real idea of what was happening to him. He couldn’t stand up without assistance. He was not allowed to walk without a walker and someone holding a gait belt around his waist. He couldn’t feed himself most of the time. All of this, when only a few months ago he could walk, still drive, and was able to calm his shaking enough to feed himself.

Perhaps, however, the thing that struck me most when I looked into his eyes, was that they were open again. They, he, received me again. After all these years. Finally, and sadly, it took things to come to this, for my brother to return and once again allow my love and compassion in.

Luckily, the weather was unseasonably warm for late February in Iowa, enabling me to take him outside. The first day we walked circles in the parking lot. Him with his walker, me holding his gate belt. We talked about Kitty Kat, his cat at home that he hadn’t seen now for three weeks. He cried because he felt he was letting Kitty Kat down.

He told me about how it was sometimes hard for him to sleep, so I introduced him to the word Om and told him it’s a magic word that can focus his mind and help him sleep. We walked around the parking lot chanting “Om.”

Later, I picked up dinner and he, my mother, and I ate in a special room at the care facility. His shaking became a never-ending body quake, preventing him from feeding himself. I sat, forcing back tears as I fed my brother his dinner, while watching my ninety-year-old mother walk to her chair, feed herself, and know it was not her that would be staying the night at the nursing home. The whole scene was mind bending because she is ninety. It felt upside down, like so many things with my parents in my life.

Agitated, Reece asked me to get a nurse and soon we were back in his room with him lying on his bed. His left arm uncontrollably rolling, he asked me, “What’s that word again, Con?”

“Word?”

“The magic word.”

“Oh, Om. Do you need to chant some oms?” I asked him.

And so, we began chanting oms, while I rubbed his convulsing arm. Seeing his diminished frame stretched out on the medical bed, took my breath away. His eyes were shut tight as he fought to stop the shaking that was completely beyond his control. Like his galactosemia. Like so much of his life.

And then, his “om” transitioned to “home.”

“Home…Home…Home…,” he said over and over again. “I just want to go home. Like Dorothy,” he said. “In the Wizard of Oz.”

I laughed an ironic laugh, “Just three clicks and you’re there.”

My brother’s speech is also affected by his Parkinson’s but in the next moment he said, with the utmost clarity, both vocally and mentally, “If only it were that easy.”

With that the dam broke, the flood of realty rushed in, and what felt like a river of tears flowed between us. It is brutal to know beyond that proverbial shadow of a doubt, a moment has been reached when there is no way, absolutely no way, to undo, to go back, to amend, to promise to do something differently, to beg, to plead, to walk away from and start anew, or to say, this is too much to think about right now, let’s revisit it in the morning. Your options are over. You are left with simply riding this one out.

He began rubbing my arm that was rubbing his arm and said, “Stay with me, Con.” I assured him that I didn’t have to leave for another hour. “Okay, okay,” he said. Seconds later, “Stay with me, Con.” I again reassured. “Okay, okay,” he said. This happened several times, as we cried over shared, unspoken loss. Finally, the time came that I did need to leave. I reassured him that I would be back the next morning.

The next day, he couldn’t walk. He could barely stand up. I wheeled him around the parking lot for at least an hour. I told him all about the story I’m writing and how the planet has three moons. “I think I would like to live there,” he said.

I told him about how I’m writing the story under a pen name, which is in part, our shared name. I told him about how my initials and our last name sound very close to a famous author’s name. “C. S. Lewis, C. S. Amos.”

“That’s odd,” he said. His body slumped and listing to the side. “You’re going to use it?” he asked.

“Yeah.”

“Good.”

I told him about the prophet Amos. How Amos believed in justice, and how the people who benefitted from the mistreatment of others didn’t like Amos, and that justice is one of the themes of my story.

Silence followed. Only the sounds of the wheelchair’s tires rolling over the detritus from snowmelt on the pavement cut through the quiet. I stopped and took the picture at the top of this post. He requested five more laps, and onward ho we went.

Looking into the brilliance of the late winter clear sky, I began to think of how burdened I have been by the weight of the name Amos. I cannot look away from injustice. My life has been paying witness to one injustice after the other being leveled on Reece. On my whole family. (If interested, it is all in my memoir.) I have spent my life watching my extended family lose its center. The tornado of my childhood dreams ripping and thrashing what once was into debris strewn across the landscape before me.

I think of how Reece arrived at this place; and how my sister, whose health is failing, has disallowed anyone or anything inside to help her process the trauma she has experienced; and how my other brother has done as much as he can to heal and escape; and how my mother, who cannot for a day, lay down her passive aggressive behavior and is unrelenting in her need to control everything about Reece; and how my father, who feels nothing for anyone or anything, or in the least is completely incapable of showing it, and how my parents have been divorced for thirty -six years and have never once had one discussion about Reece; and how, by being trapped in the dysfunctional dynamics or our parents, my birth family is unraveling and flying apart at the seams.

These are the things that happen to unhealed people. To people whose emotions are unevolved and trapped inside trauma. To people who don’t seek help to separate out when they’ve been victimized and when they lean on their victimhood like a crutch. To people who are desperately needy of compassion and release but hold closed, with a fierce, tenacious grip, the walls surrounding their heart, preventing help, love, compassion, and rescue from entering.

This is what happens when people believe there is no other way.

I have spent my life metaphorically in the basement of my childhood home seeing the tornado coming, believing that the tornado was coming, begging and pleading them all to come to the basement. But none of them would look out the window, which allowed none of them to see, and therefore, they didn’t have to believe. They didn’t come to the basement because they couldn’t, they didn’t come because they wouldn’t. Like the prophet Amos, my message was rejected. Not for being a shepherd, but for being the youngest.

The last day I visited my brother, he told me about a dream he had during the night. “We kept finding each other and losing each other. Over and over again,” he said through tried speech.

“Did we find each other in the end?” I asked.

“No,” he said.

He looked at me with the lifted, wondering brow and the countenance my grandfather (whom Reece looks like) would have when he was telling me about something that was simply a fact that could not be changed, rendering it neither bad nor good, but making it clear it was something we had to live with; so therefore, best to make peace with.

“We never did,” he said, reaching for my hand.

Rubbing his thumb over the back of my hand, he said, “Funny how real dreams can be sometimes.”

As I said goodbye before leaving to come home, we were unable to let go of one another. We were unable to stop crying. We were unable to allow that this is what all the pain and suffering of our lives had come to. Finally, I turned and left my brother alone to his small room, to all the thoughts that were in his mind, and to his Parkinson’s knowing there was nothing I could do about any of it.

On my drive back from Iowa to Milwaukee, I thought about all the times I have, like Amos the prophet, tried to help my parents and siblings change track. I have repeatedly said, “Things don’t need to be this way.” But now, I suppose, perhaps they do, for them.

While heading towards Iowa City, I realized why I have so passionately desired my family to heal. While I know that healing and healthy behavior would be better for all of us, my therapist’s words smacked me between the eyes and I heard her ask, as she had many times when I was seeing her, “What is in this for you?”

I asked for the answer, and it came quickly. My family members have been in shock from trauma for decades. When people are in shock, they are not conscious of what they are doing. My family has not been conscious for decades. I realized that my motivation, my selfish desire for them all to get well, stemmed from not wanting to pay witness to that moment when the consciousness/reality came flooding in that they could have done things differently. That they could have gone to the basement. But because of the tenacity with which my family members have clung to not needing help, mentally, emotionally, medically, or otherwise, and the degree to which they have cut off love and compassion from their lives, consciousness would/will inevitably invade when it was/is too late to do anything about it.

I have been in the basement, knowing the tornado is coming, begging them to come down with me, my whole life. It has never stopped. The dreams might have, but my desire to save them never has. I have not wanted to see my family lying in the rubble when they realize they never needed to be there. But here we are. I couldn’t save them, then. I can’t save them, now. Oh, the hubris I possessed.

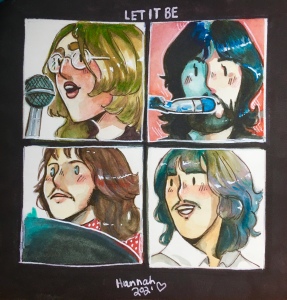

I turned northeast onto Highway 151, crying with the lyrics to “Let It Be” playing on endless loop in my head.

Click here to watch The Beatles’ official “Let It Be” video.

There will be answers for my family, if they chose to ask the questions. For the first time in my life, I fully embraced that while we have shared experiences, we do not have shared questions, and therefore, we don’t have shared answers. All that is in my power, is to grant them compassion for whatever this life’s journey is, hoping for them, they will discover it before it is too late. Knowing that I have no providence over their lives, I must adopt my grandfather’s lifted, wondering brow and let it be.

Thank you for reading.

Kim, Thank you so much for reading and commenting and for holding us in your thoughts. Hugs, Connie

LikeLike

An amazing post. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thanks for stopping by and commenting, Jeannee!

LikeLike